RIP-K.G.Subramanyan

An artist who broke down boundaries

[TD="class: articleheader"][/TD]

[TD="class: story, align: left"]

KG Subramanyan

KG Subramanyan

The path-breaking and protean artist savant, Kalpati Ganapati Subramanyan, who died in Vadodara at the age of 92 on Wednesday afternoon, had embraced world culture, but his aesthetic sensibility was rooted in traditions as he made no distinction between classical Indian art and the country's folk culture.

He inspired great admiration that almost bordered on reverence, yet at heart he was a no-nonsense man with a sly sense of humour that was irreverent at times.

"Manida" or "KG", as he was popularly known, came of age as an artist at Kala Bhavan in Santiniketan and was very close to Benode Behari Mukherjee and Ramkinkar Baij. Yet, when he left Santiniketan and shifted to Vadodara in the winter of his life, he did not spare the "ashram" that Rabindranath had established, describing it as "a carnival site for affluent people in Calcutta".

KG was born in 1924 at Mahe, a French colony on the west coast of Kerala, but was arrested and banned from further education for participating in the Quit India Movement. However he was acquainted with modern European masters and had seen reproductions of the works of Nandalal Bose and Tagore. Sculptor Debi Prosad Roy Chowdhury was impressed by some of his works, and he steered his career from politics to art as he joined Santiniketan.

As he embarked on his professional career as an artist, KG experimented in myriad forms like terracotta murals, reverse glass painting, enamel painting, toymaking, and weaving. He made toys with wood and leather, rather unusual for our country. One of his most significant murals was based on Tagore's play, King of the Dark Chamber . KG's mural was a visual transcription and free restructuring of the episodes of the play.

When it came to terracotta, Subramanyan allowed the medium to speak its tongue. He created organic images which he creased and folded with clay, and he often used tablets of clay to tell stories.

KG was an exceptionally gifted writer and had produced several books and treatises on aesthetics that reflected his deep understanding of Indian culture and vast learning. He was a brilliant writer of stories and rhymes for children which he often illustrated. He believed that children did not need lollipops, and there were often dark shades in what he wrote for them.

In his reverse glass paintings he transformed sensuous images of his terracottas into glittering bazaar icons gilded with gold. He drew upon the beauties of Kalighat patas to create seductresses often accompanied by their pets. His wit sparkled in these works. His career having spanned several decades, it saw several radical transformations. His ideas, style, and materials used, everything underwent gradual but radical changes.

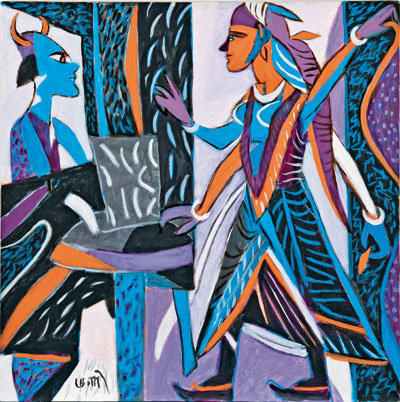

His art was a celebration of his voracious appetite for all influences both foreign and indigenous. Picasso, patachitras , bazaar prints, African masks and Tanjore paintings appear and make comebacks with renewed vigour, every time in a new avatar.

There was a strong decorative element in all of KG's compositions, but he did not use this for mere embellishment. They gave an ironic edge to his work just in the same way that deities and fantastic creatures do when they make an appearance in otherwise realistic situations, blurring the line between the real and irreal. If we examine his career, Subramanyan was always breaking down boundaries that we erect between the folk and the hieratic, between global cultures and geographical confines.

KG was a highly skilled draughtsman and anatomy was his strong point. So each part of the body would have the freedom of moving independently like a puppet, the talpatar sepai still sold in Santiniketan. So his drawings were both facile and have an inherent decorative element. Even when he distorted his figures, they did not violate the rules of construction.

KG Subramanyan was a Padma Vibhushan. He was invited to exhibit his works at documenta, the major exhibition of contemporary art at Kassel in Germany next year.

[/TD]

An artist who broke down boundaries

[TD="class: articleheader"][/TD]

[TD="class: story, align: left"]

The path-breaking and protean artist savant, Kalpati Ganapati Subramanyan, who died in Vadodara at the age of 92 on Wednesday afternoon, had embraced world culture, but his aesthetic sensibility was rooted in traditions as he made no distinction between classical Indian art and the country's folk culture.

He inspired great admiration that almost bordered on reverence, yet at heart he was a no-nonsense man with a sly sense of humour that was irreverent at times.

"Manida" or "KG", as he was popularly known, came of age as an artist at Kala Bhavan in Santiniketan and was very close to Benode Behari Mukherjee and Ramkinkar Baij. Yet, when he left Santiniketan and shifted to Vadodara in the winter of his life, he did not spare the "ashram" that Rabindranath had established, describing it as "a carnival site for affluent people in Calcutta".

KG was born in 1924 at Mahe, a French colony on the west coast of Kerala, but was arrested and banned from further education for participating in the Quit India Movement. However he was acquainted with modern European masters and had seen reproductions of the works of Nandalal Bose and Tagore. Sculptor Debi Prosad Roy Chowdhury was impressed by some of his works, and he steered his career from politics to art as he joined Santiniketan.

As he embarked on his professional career as an artist, KG experimented in myriad forms like terracotta murals, reverse glass painting, enamel painting, toymaking, and weaving. He made toys with wood and leather, rather unusual for our country. One of his most significant murals was based on Tagore's play, King of the Dark Chamber . KG's mural was a visual transcription and free restructuring of the episodes of the play.

When it came to terracotta, Subramanyan allowed the medium to speak its tongue. He created organic images which he creased and folded with clay, and he often used tablets of clay to tell stories.

KG was an exceptionally gifted writer and had produced several books and treatises on aesthetics that reflected his deep understanding of Indian culture and vast learning. He was a brilliant writer of stories and rhymes for children which he often illustrated. He believed that children did not need lollipops, and there were often dark shades in what he wrote for them.

In his reverse glass paintings he transformed sensuous images of his terracottas into glittering bazaar icons gilded with gold. He drew upon the beauties of Kalighat patas to create seductresses often accompanied by their pets. His wit sparkled in these works. His career having spanned several decades, it saw several radical transformations. His ideas, style, and materials used, everything underwent gradual but radical changes.

His art was a celebration of his voracious appetite for all influences both foreign and indigenous. Picasso, patachitras , bazaar prints, African masks and Tanjore paintings appear and make comebacks with renewed vigour, every time in a new avatar.

There was a strong decorative element in all of KG's compositions, but he did not use this for mere embellishment. They gave an ironic edge to his work just in the same way that deities and fantastic creatures do when they make an appearance in otherwise realistic situations, blurring the line between the real and irreal. If we examine his career, Subramanyan was always breaking down boundaries that we erect between the folk and the hieratic, between global cultures and geographical confines.

KG was a highly skilled draughtsman and anatomy was his strong point. So each part of the body would have the freedom of moving independently like a puppet, the talpatar sepai still sold in Santiniketan. So his drawings were both facile and have an inherent decorative element. Even when he distorted his figures, they did not violate the rules of construction.

KG Subramanyan was a Padma Vibhushan. He was invited to exhibit his works at documenta, the major exhibition of contemporary art at Kassel in Germany next year.

[/TD]

Last edited: