[h=1]The curious case of high blood pressure around the world[/h]A new study challenges received wisdom about the causes of high blood pressure

[h=3]Graphic detail[/h]Jan 13th 2017by THE DATA TEAM

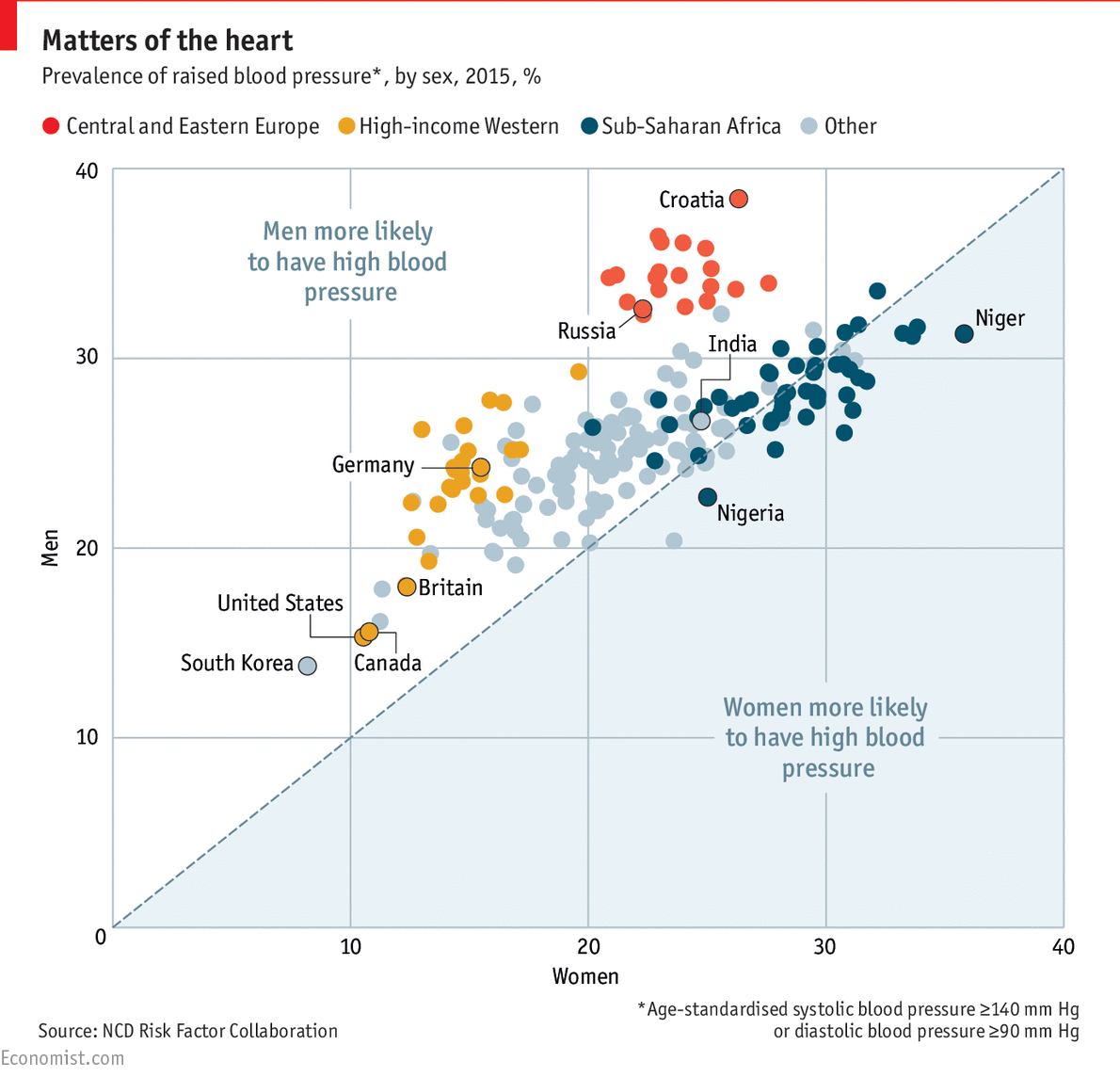

ONE in eight deaths worldwide is due to high blood pressure. The condition is the main risk factor for heart and kidney disease, and it greatly increases the chances of a stroke. A new study published in the Lancet, a medical journal, shows how common it is—and challenges some received wisdoms.

Globally, about a fifth of women and a quarter of men have high blood pressure. It is commonly thought of as a disease of affluence. But the data say otherwise. Central and eastern Europe have the highest rates for men, while the highest rates for women are in sub-Saharan Africa. Prevalence is lowest in rich Western and Asian countries, including South Korea, America and Canada. In only 36 countries high blood pressure is more common in women than in men. Nearly all of them are in Africa.

The well-known causes of high blood pressure include lack of exercise, being overweight, and diets that include too much salt and alcohol and not enough fruit and vegetables (which are a source of potassium, linked with lower blood pressure). More recently, studies have implicated early-life nutrition and exposure to lead, air pollution and noise as things that may push blood pressure up later in life. The lack of a year-round supply of fresh produce in eastern Europe could be one reason why rates there are so high. The greater parity between men and women in Africa could be due to poor nutrition in utero and in early childhood. Trends over time also suggest that the role of nutrition and a cleaner environment may be more important than previously thought: the study found that blood-pressure levels in rich countries had begun to fall before detection and treatment became widespread, and continued to fall even as waistlines grew wider and wider. All of this suggests that efforts to curb blood pressure need to start much earlier in life and go beyond treatment and changes in individual lifestyles.

https://www.economist.com/blogs/graphicdetail/2017/01/daily-chart-12?fsrc=scn/tw/te/bl/ed/

[h=3]Graphic detail[/h]Jan 13th 2017by THE DATA TEAM

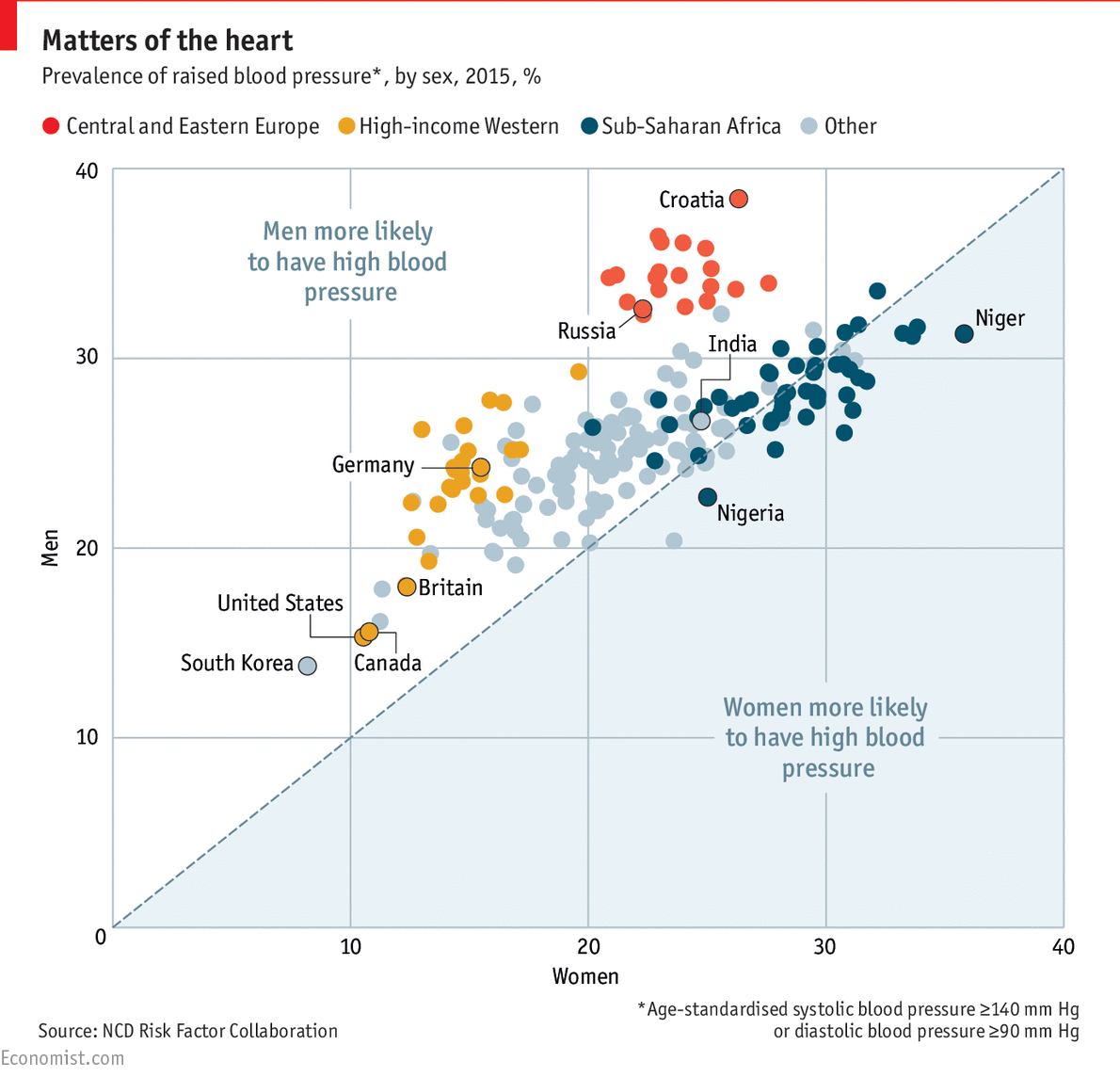

ONE in eight deaths worldwide is due to high blood pressure. The condition is the main risk factor for heart and kidney disease, and it greatly increases the chances of a stroke. A new study published in the Lancet, a medical journal, shows how common it is—and challenges some received wisdoms.

Globally, about a fifth of women and a quarter of men have high blood pressure. It is commonly thought of as a disease of affluence. But the data say otherwise. Central and eastern Europe have the highest rates for men, while the highest rates for women are in sub-Saharan Africa. Prevalence is lowest in rich Western and Asian countries, including South Korea, America and Canada. In only 36 countries high blood pressure is more common in women than in men. Nearly all of them are in Africa.

The well-known causes of high blood pressure include lack of exercise, being overweight, and diets that include too much salt and alcohol and not enough fruit and vegetables (which are a source of potassium, linked with lower blood pressure). More recently, studies have implicated early-life nutrition and exposure to lead, air pollution and noise as things that may push blood pressure up later in life. The lack of a year-round supply of fresh produce in eastern Europe could be one reason why rates there are so high. The greater parity between men and women in Africa could be due to poor nutrition in utero and in early childhood. Trends over time also suggest that the role of nutrition and a cleaner environment may be more important than previously thought: the study found that blood-pressure levels in rich countries had begun to fall before detection and treatment became widespread, and continued to fall even as waistlines grew wider and wider. All of this suggests that efforts to curb blood pressure need to start much earlier in life and go beyond treatment and changes in individual lifestyles.

https://www.economist.com/blogs/graphicdetail/2017/01/daily-chart-12?fsrc=scn/tw/te/bl/ed/