people in tamilnadu decide on one of the dravidian parties wondering who is less corrupt or criminal besides working out the value of freebies offered.someone says my hands are clean,vote for me ,why not?Will the public of Tamil Nadu accept AAP as an alternative…..?

It is to be seen how far AAP make its presence in Tamil Nadu politics as it has to pass through the bottle necks like strong affiliation of public towards caste,

money power, brain washing strategy adapted by hardcore politicians and tall promises.

Of course public have already forgotten ‘ 2 G’,etc.

-

This forum contains old posts that have been closed. New threads and replies may not be made here. Please navigate to the relevant forum to create a new thread or post a reply.

-

Welcome to Tamil Brahmins forums.

You are currently viewing our boards as a guest which gives you limited access to view most discussions and access our other features. By joining our Free Brahmin Community you will have access to post topics, communicate privately with other members (PM), respond to polls, upload content and access many other special features. Registration is fast, simple and absolutely free so please, join our community today!

If you have any problems with the registration process or your account login, please contact contact us.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

World's biggest election on; Are you ready to cast your vote?

- Thread starter vgane

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

poor mamata, hazare has taken her for a ride.the wily character saw that there were no crowds and backed out.only kejriwal can manage him. you have to be a marwari[eetikaran] to get something out of anna.Seeing the poor response in a Delhi rally called by Mamata, Anna cancelled the meeting..Looks like he is now cosying up to BJP

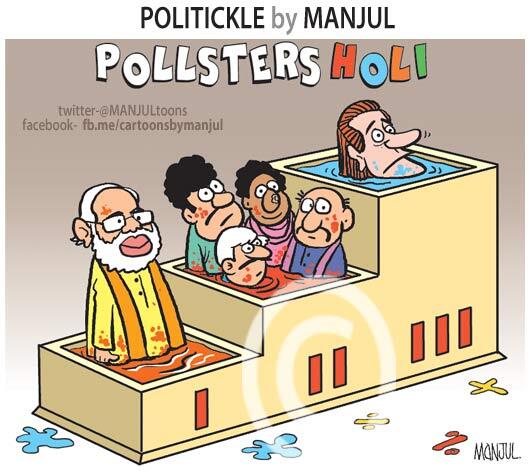

Cast(e) the votes lol!! One day Modi is champion of all sections of society, other day he's an OBC. Congress has no allies. JJ and Deve Gowda want to be PM. More interesting than a Sun TV soap.

prasad1

Active member

Modi, India's Favorite Son, Needs a Voice

The right reforms could create an additional 40 million nonfarm jobs by 2022, according to a report from the McKinsey Global Institute. But they will require hard choices, not simply an ability to push investment deals through. Whoever becomes prime minister will have to address fundamental questions of labor and land reforms, the states' relationships with the central government, taxes, infrastructure investment, health care and the yawning demand for vocational training. The new leader will have to lay the groundwork for a true manufacturing sector, rebalance investment in agriculture and vastly improve the delivery of government services. Ideas and policies to meet all these challenges exist, but Modi has avoided choosing among them -- not least because of differences of opinion within his party.

Modi’s second, and arguably more important, failing concerns the 2002 riots in Gujarat, where more than 1,000 people, mostly Muslims, were killed and several women raped while police and state officials stood by. Modi, whose base includes the Hindu militant groups accused of leading the attacks, has never forthrightly apologized nor taken responsibility for the brutality on his watch.

When the subject comes up, Modi's supporters cite the "clean chit" given to him by Indian judges, who ruled that he had not prevented aid from reaching Muslim riot victims. That doesn’t remotely lessen his responsibility for the officials under him, some of whom have received prison sentences for their role in the violence. Modi himself refuses even to entertain questions about the incident. On March 3, he canceled an appearance at a town hall where he could not control the questioning. This is cowardice, not leadership.

Modi is essentially telling voters that they can count on him to get the economy moving again, and should therefore drop any lingering suspicion that he is an autocrat or an anti-Muslim bigot. Indians are entitled to know how he plans to fulfill his promises.

The right reforms could create an additional 40 million nonfarm jobs by 2022, according to a report from the McKinsey Global Institute. But they will require hard choices, not simply an ability to push investment deals through. Whoever becomes prime minister will have to address fundamental questions of labor and land reforms, the states' relationships with the central government, taxes, infrastructure investment, health care and the yawning demand for vocational training. The new leader will have to lay the groundwork for a true manufacturing sector, rebalance investment in agriculture and vastly improve the delivery of government services. Ideas and policies to meet all these challenges exist, but Modi has avoided choosing among them -- not least because of differences of opinion within his party.

Modi’s second, and arguably more important, failing concerns the 2002 riots in Gujarat, where more than 1,000 people, mostly Muslims, were killed and several women raped while police and state officials stood by. Modi, whose base includes the Hindu militant groups accused of leading the attacks, has never forthrightly apologized nor taken responsibility for the brutality on his watch.

When the subject comes up, Modi's supporters cite the "clean chit" given to him by Indian judges, who ruled that he had not prevented aid from reaching Muslim riot victims. That doesn’t remotely lessen his responsibility for the officials under him, some of whom have received prison sentences for their role in the violence. Modi himself refuses even to entertain questions about the incident. On March 3, he canceled an appearance at a town hall where he could not control the questioning. This is cowardice, not leadership.

Modi is essentially telling voters that they can count on him to get the economy moving again, and should therefore drop any lingering suspicion that he is an autocrat or an anti-Muslim bigot. Indians are entitled to know how he plans to fulfill his promises.

I am wary of reports of american think tanks and dubious consultants from western countries.

Modi may talk of development but the basic agenda is hinduthva under the table. if he comes to power,he will push RSS men into all institutions, education will have a more hindu tilt ,more imposition of hindi, vande mataram,chaddiwalas in schools and colleges. all sundry sadhus will take centre stage. minorities will get further marginalised and it will be ayodhya and ram mandir again in addition to patel statues and the like,ladies emancipation will take a backseat and hindu activists will deny women of basic rights .I would not be surprised if they come out with a dress code and talibanise indian society.

as far as econmics goes, once in power at the centre, he will no longer talk of federal structure or right of states. his development model will support a few business houses who have bank rolled him. Tax reforms -might get DTC and GST in course of time and some sops to middle class such as income tax reliefs and pay revisions. whether ,he will be able to contribute to skill development or create jobs in rural or urban sector is doubtful. farm sector holds a great potential . whether he will go in for land reforms in rural areas like the left in west bengal is doubtful.infra in india is a black hole. crores sunk into roads and highways and high rises are white elephants with only leakage and no development.health care is dead for the poor.he might create national institutions for health care and education catering to the affluent. poor will have a bad time with his labour policies.

anyway it will be a rickety govt with bare majority .this may act as a check on his autocratic ways

Modi may talk of development but the basic agenda is hinduthva under the table. if he comes to power,he will push RSS men into all institutions, education will have a more hindu tilt ,more imposition of hindi, vande mataram,chaddiwalas in schools and colleges. all sundry sadhus will take centre stage. minorities will get further marginalised and it will be ayodhya and ram mandir again in addition to patel statues and the like,ladies emancipation will take a backseat and hindu activists will deny women of basic rights .I would not be surprised if they come out with a dress code and talibanise indian society.

as far as econmics goes, once in power at the centre, he will no longer talk of federal structure or right of states. his development model will support a few business houses who have bank rolled him. Tax reforms -might get DTC and GST in course of time and some sops to middle class such as income tax reliefs and pay revisions. whether ,he will be able to contribute to skill development or create jobs in rural or urban sector is doubtful. farm sector holds a great potential . whether he will go in for land reforms in rural areas like the left in west bengal is doubtful.infra in india is a black hole. crores sunk into roads and highways and high rises are white elephants with only leakage and no development.health care is dead for the poor.he might create national institutions for health care and education catering to the affluent. poor will have a bad time with his labour policies.

anyway it will be a rickety govt with bare majority .this may act as a check on his autocratic ways

C

CHANDRU1849

Guest

In tamilnadu,AAp has enrolled 3 lakh members.whether the party can make a difference is doubtful. some congress sympathisers can join them as they have no future in congress and AAP is a party without corruption taint.for brahmins also it is an alternative

Majority of Brahmins, both Iyers (unfortunately) and Iyengars, in TN think that their problems will be totally solved if JJ takes the centre stage, instead of working together.

The belief still goes on and will go on for ever.

There are zillion clues to prove kejri is Sonia's plant. All his chelas, NAC, and NGOs have said more than once that their target is modi and attack on congress is a smokescreen.

Now Modi

has to face Kejriwal in Varanasi...If Kejriwal was against corruption why has he not fought against Sonia in Rae Bareli..This shows he is a stooge of Congress...Last 10 years of UPA rule is a disaster and Indian money was siphoned off by the looters!

In Telengana TRS ditches Congress! Smart move by Rao to keep both UPA & NDA options open for any post poll maneuvering!

TRS rules out alliance with Congress in AP - The Hindu

TRS rules out alliance with Congress in AP - The Hindu

the infighting in BJP which is coming out in finalisation of contestants for seats to be contested in UP may hurt its poll prospects .for BJP it is the enemy within. UP is a difficult state. as poll draws near . bjp appears to be losing ground due to extraneous factors. out of 130 seats in south, bjp can hope for some in karnataka due to reddy bothers and yeddiyurappa -very corrupt elements.otherwise it is only northern states -of gujerat,MP ,rajasthan. the 50 seats out of 80 in UP appears to be distant as it stands now.In bihar also the minorities and rjd will have a say. unless they carry UP,it is a lost cause. bjp + cannot cross 220 seats or so

AK is nobody's plant. he is in varanasi for national visibility and to show only he has the courage to take on modi.he has hogged tv space free by his new antics everyday.he was trying to push shazia ilmi to fight sonia. but that lady refused to become a scapegoat having lost once in delhi.There are zillion clues to prove kejri is Sonia's plant. All his chelas, NAC, and NGOs have said more than once that their target is modi and attack on congress is a smokescreen.

he will find someone -preferably a lady to take sonia on.aap may not win in a big way. definitely AAP will leave a mark on the country looking for an alternative. AK will play for minority votes in varanasi and other places in UP and spoil chances of MSY,Mayawati and congress.more than modi

Capt Gopinath (Erstwhile owner of Air Deccan & member of AAP has voiced his concern about the direction that AAP has taken!

Blog: Arvind Kejriwal crosses the line with 'paid media' remarks | NDTV.com

Blog: Arvind Kejriwal crosses the line with 'paid media' remarks | NDTV.com

C

CHANDRU1849

Guest

MK's strategy in forging alliance is really puzzling. What is his idea? Though he made some positive statements about NAMO, he has not gone with BJP and also sidelined Congress, but has, instead, preferred some Dalit and Muslim outfits. As a result, he has indirectly helped to improve the chances of JJ.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Latest posts

-

-

-

உலகம் போற்றும் அருளாளர்களில் ஆதிசங்கரர் முதன்மையானவர்.

- Latest: Padmanabhan Janakiraman

-

Latest ads

-

Free [Bride Wanted] Bride WantedLooking for Bride - Family Oriented and brought up from Cultured Family

- SRIKANT S -(Bride Wanted) (+0 /0 /-0)

- Updated:

- Expires

-

-

Free [Bride Wanted] TAMIL BRAHMIN VADAMA BRIDE WANTEDMust to be willing to relocate to Bengaluru Must be willing to accommodate joint family

- self today (+0 /0 /-0)

- Updated:

- Expires

-

Wanted [Cook Wanted] Wanted cook for Home at Gandhipuram Coimbatore. Decent Salary offeredHi, we need a female Brahmin cook for home ( 5 members family) at Coimbatore. Morning and...

- gchitra (+0 /0 /-0)

- Updated:

-

Wanted [Cook Wanted] Vegetarian tamil cookBangalore Bannerghatta Main road

- nschander (+0 /0 /-0)

- Updated:

- Expires