In rural Bihar, where one doctor services 43,788 people (the WHO guidelines advise one doctor per 1,000 people), most said they had little hope of proper treatment if they fell ill with Covid-19, with hospitals sometimes hundreds of miles away. The mechanisms for disease surveillance and death reporting in deprived rural communities are also very poor, meaning the true toll of the pandemic may never be known.

The absence of technical trained staff has been a major issue for Bihar during the pandemic. While 207 ventilators have been given to the state, they have been gathering dust because no-one is trained to operate them. Images have also emerged this week of Covid-19 patients being treated on the floor of Bihar government hospitals because they are so overburdened.

In Umakant’s village, which has a population of 1,000, 20 villagers have recently tested positive. Resident Akshay Singh said nearby hospitals did not have the doctors, the oxygen or the medicines to treat Covid-19 patients. “You can imagine the lack of availability of beds and oxygen cylinders in the hospitals,” he said.

Even as districts are accused of concealing the true death toll, Covid fatalities are rising at record rate in Bihar. In the year from March 2020 when the pandemic first hit, to March this year, 1,578 lives were lost to the virus in Bihar, officially. But in just the past 36 days, there have already been 1,499 recorded coronavirus deaths in the state, many from rural areas.

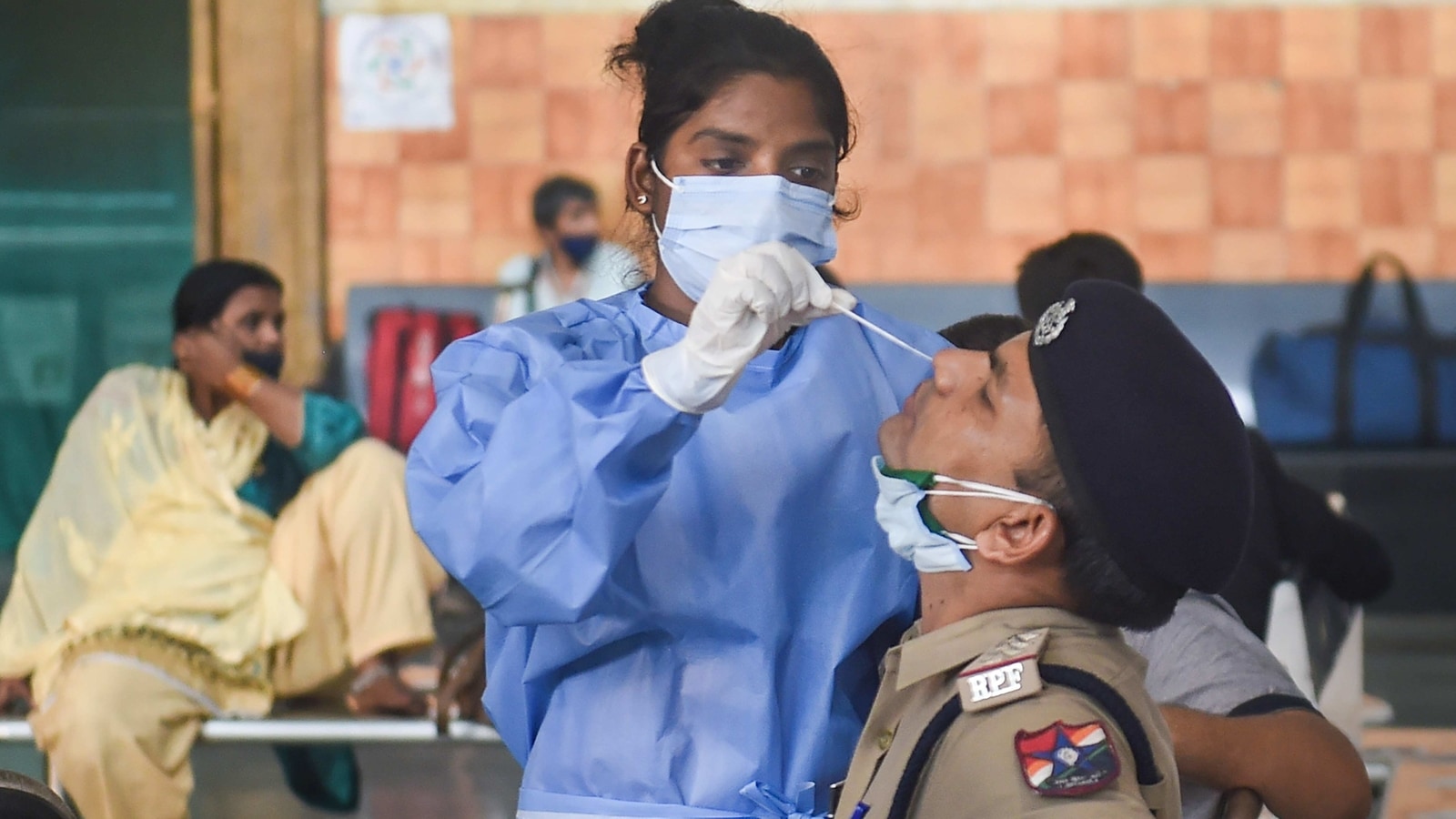

The local civil surgeon, a senior medic in the area, Dr Sudhir Mahato said the virus was now decimating rural villages and they were struggling to have the capacity to test everyone. As hundreds queued every day at a local healthcare centre for tests, many feared the centres themselves had now become super-spreader venues.

In Salempur village, in northern Bihar’s Gopalganj district, the spread of the virus has been brutal, claiming 10 lives in the space of a fortnight.

“The overall situation looks very critical,” said Dhananjay Singh, the chief of Salempur village council. His younger brother Sanjay Singh, 48, was among the dead.

“My brother came down with a fever and throat infection so we got him admitted to a local government hospital in Gopalganj town and he was found positive for Covid-19. But they lacked even the most basic facilities, so his condition deteriorated quickly,” said Singh. “Eventually, we rushed him to a private hospital in neighbouring Uttar Pradesh but it was too late, he died.”

The state is currently under lockdown and the Bihar health minister Mangal Pandey insisted more doctors and healthcare staff were being recruited temporarily to meet the growing need.

But Suresh Baitha, a ward official from Gopalganj district, said that an issue they were encountering was that hospital staff were treating Covid patients as “social outcasts” and did not want to touch them, particularly as they were not being given adequate protective equipment. General medicines and vitamins recommended for Covid treatment had also all run out, he added.

“The major problem is that the hospital staff don’t want to touch the Covid patients fearing they themselves could get infected. The result is that the majority of the patients don’t want to go to hospital and by the time they are admitted there, their condition becomes critical,” said Baitha.

He was echoed by the local civil surgeon Dr Yogendra Bhagat. “The problem is that no-one want to work at this critical time,” he said. “We are even facing problems in disposal of the Covid bodies.”

The pandemic overwhelming the big cities is reaching areas of Bihar where there is one doctor for 40,000 people

www.theguardian.com